Understanding Religion as a Social Construct: Perspectives, Evidence, and Practical Implications

Introduction

Religion is a topic that sparks debate, reflection, and inquiry across societies. One of the most discussed questions among scholars, practitioners, and laypeople alike is whether religion is a social construct . This article provides an in-depth analysis of the concept, examines the evidence and arguments for and against this viewpoint, and offers practical guidance for engaging with religious beliefs and institutions in contemporary society.

What Does It Mean to Call Religion a Social Construct?

To describe religion as a social construct is to claim that religion is not an inherent or natural feature of human existence , but rather a phenomenon that arises from collective human agreements, historical developments, and social processes. Social constructionism, as a theoretical perspective, argues that many concepts and institutions, including religion, are created, maintained, and transformed by people in specific times and places [3] .

Source: animalia-life.club

Social constructionists assert that:

- Religion is defined and redefined by communities and cultures.

- The meaning, significance, and practices of religion change across societies and historical periods.

- There is no single, universally accepted definition of religion.

For example, the status of Scientology as a religion has been contested in different countries, showing how power and cultural context influence what is recognized as a religion [1] .

Source: animalia-life.club

Evidence and Arguments: Is Religion a Social Construct?

The debate over whether religion is a social construct centers on several lines of evidence and reasoning:

Historical and Sociological Perspectives

Social constructionism suggests that religious beliefs, texts, and rituals are products of human ingenuity and collective experience. Important religious texts, such as the Bible or the Quran, were written, edited, and canonized by human communities over centuries [4] . The rules, symbols, and organizational structures we associate with religion are shaped by social, political, and cultural forces.

One prominent example is the way religious movements adapt or reinterpret doctrines in response to societal changes, such as the role of women or attitudes toward science. This adaptability highlights the constructed nature of religious meaning.

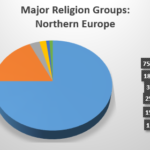

Anthropological and Cross-Cultural Evidence

Anthropological research shows that religious practices and beliefs vary widely among cultures. What counts as ‘religion’ in one culture may not be recognized as such in another. Definitions are often negotiated and contested within and between societies [1] . For instance, indigenous spiritualities may not fit Western definitions of religion but are deeply meaningful to practitioners.

Debates and Counterarguments

While social constructionism provides a robust framework, some argue that religion also reflects universal psychological or existential needs-such as the search for meaning, community, or explanations for the unknown. Others suggest that certain core elements, such as belief in supernatural agents, appear across diverse societies and may be rooted in human cognition.

Recent research complicates the debate: a

Nature

study found that complex societies tend to develop moralizing gods only after reaching a certain size, suggesting that some forms of religion might emerge as social mechanisms to promote group cohesion and regulate behavior

[2]

.

How Is Religion Constructed in Society?

Social construction of religion occurs through dynamic processes:

- Interpretation: Individuals and groups interpret symbols, texts, and traditions in ways that reflect their circumstances and values.

- Institutionalization: Religious organizations codify beliefs, set norms, and create rituals that reinforce a shared identity.

- Legal and Political Recognition: Governments and legal systems may grant or deny religious status to groups, influencing how religion is defined and practiced.

- Socialization: People learn religious beliefs and practices through family, education, and participation in community life.

For example, changing laws about religious freedom or public holidays can reshape the public perception and influence of religion.

Practical Implications: Engaging with Religion as a Social Construct

Understanding religion as a social construct can help individuals, organizations, and policymakers navigate the complexities of religious diversity and change. Here are some steps and strategies for practical engagement:

1. Recognize the Diversity of Religious Experience

Approach religious beliefs and practices as dynamic and multifaceted. Avoid assuming that all religions function the same way or that one definition applies everywhere. Engage with people and communities on their own terms, seeking to understand their perspectives.

2. Navigate Legal and Institutional Contexts

If you are part of an organization or community seeking official recognition for a religious group, research the relevant government agency or legal body in your region. Each country or state has different procedures. For example:

- Contact your local government office or department responsible for religious affairs for guidance on registration or recognition processes.

- Consult with legal experts or interfaith organizations for advice on navigating complex regulations.

Be prepared to provide information about your group’s beliefs, practices, and organizational structure, as these are often required for recognition.

3. Engage in Dialogue and Education

Promote interfaith and intercultural dialogue to foster understanding and reduce conflict. Educational programs, community forums, and workshops can help demystify religious differences and emphasize shared values.

Consider collaborating with established academic institutions, such as university religious studies departments, for resources and expertise. You can find relevant courses and materials by searching for “Sociology of Religion” or “Religious Studies” at major universities.

4. Address Challenges and Controversies

Recognizing religion as a social construct can raise challenges, such as disputes over what counts as a legitimate religion or tensions between religious and secular values. Solutions include:

- Establishing clear, inclusive criteria for recognizing religious groups.

- Creating spaces for respectful dialogue and negotiation.

- Providing mediation services for conflicts involving religious identities.

5. Consider Alternative Approaches

Not everyone agrees that religion is purely a social construct. Some prefer functionalist or substantive definitions, focusing on the unique roles religion plays or the specific beliefs it entails. Others emphasize spiritual or mystical experiences that transcend social categories. When working with diverse populations, consider multiple frameworks and remain open to different perspectives.

How to Find More Information and Get Involved

If you wish to learn more or participate in discussions about religion as a social construct, you can:

- Search for academic articles or books using terms like “social constructionism and religion” or “sociology of religion.” University libraries and platforms such as JSTOR or Google Scholar provide broad access to scholarly work.

- Join local or online interfaith groups to share experiences and perspectives.

- Attend public lectures or webinars offered by reputable universities or religious studies centers.

- Consult your local community center or government agency for information on religious diversity initiatives and support services.

For official recognition or legal guidance, always start by contacting the relevant government department or searching for your country’s department of religious affairs.

Key Takeaways

The claim that religion is a social construct is supported by substantial evidence from sociology, history, anthropology, and legal studies. However, the debate remains open, with alternative explanations and ongoing research. By understanding religion as a dynamic, constructed phenomenon, individuals and organizations can better respect diversity, navigate legal frameworks, and contribute to constructive dialogue in society.