Religious Life in Colonial South Carolina: Diversity, Law, and Legacy

Introduction: Religion as a Cornerstone in Colonial South Carolina

From its earliest days, religion played a central role in the social and political fabric of South Carolina. The colony’s founders, the Lords Proprietors, envisioned a community grounded in religious order, yet also recognized the practical benefits of tolerating a range of Protestant beliefs. This vision, however, coexisted with a legal system that privileged the Church of England and marginalized both non-Anglican dissenters and non-Christian faiths. Understanding the religious landscape of colonial South Carolina is essential for grasping its cultural development and the enduring legacies of its laws and customs.

The Establishment of Anglicanism: Law and Practice

When the Carolina Colony was founded in 1670, the Lords Proprietors declared the Church of England (Anglicanism) as the colony’s “only true and orthodox” faith. This official status was codified with the 1706 Church Act, which created ten religious parishes, mandated the construction of churches and parsonages, and imposed a tax to support Anglican clergy. Membership in the Church of England was thus closely linked to political rights and social standing, giving Anglicans a privileged position in colonial society [1] .

Nonetheless, the colony’s leadership also sought to attract settlers of various Protestant backgrounds. This pragmatic approach meant that, despite Anglican dominance, the law allowed for the presence of Presbyterians, Quakers, Huguenots, Anabaptists, and Congregationalists. A 1761 Act even offered incentives for foreign Protestants to settle in South Carolina, reflecting a willingness to prioritize economic growth over strict religious uniformity [3] .

Protestant Dissenters and Religious Tension

The presence of non-Anglican Protestants-often called dissenters-was a defining feature of the colony’s religious life. These groups included Scottish Presbyterians, French Huguenots fleeing persecution, and English Baptists and Quakers. While they were tolerated to a degree, their political participation and religious practices were often restricted by the Anglican establishment. Dissenters sometimes faced legal or social discrimination, yet over time they built their own congregations and exerted increasing influence, especially in the colony’s interior regions [1] .

By the mid-1700s, tensions between Anglicans and dissenters led to legal reforms. The 1778 South Carolina Constitution marked a significant shift: it replaced Anglicanism with Christianity as the officially recognized religion, extended equal legal status to all Protestant churches, and eliminated tax-based support for clergy. This move was championed by dissenting leaders like Presbyterian minister William Tennent, who advocated for liberty of conscience within a broadly Christian context [5] .

Source: thestudyaide.blogspot.com

African and Indigenous Religious Traditions

The religious landscape of colonial South Carolina was further shaped by the practices of enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples. Africans brought to the colony often practiced religions rooted in West and Central African traditions, such as Bakongo spirituality. Some enslaved individuals, particularly from the Senegambia region, were Muslims who maintained elements of their faith, such as praying facing east. Over time, many enslaved people were converted-sometimes forcibly-to Christianity, blending African spiritual elements with Protestant worship to create unique religious expressions, such as the Gullah culture and distinctive black church traditions [4] .

Indigenous religious practices also persisted, although colonial authorities and settlers often regarded Native beliefs as inferior and sought to suppress them. The diversity of religious traditions contributed to a dynamic, sometimes contentious, environment where different faiths interacted, clashed, and occasionally blended.

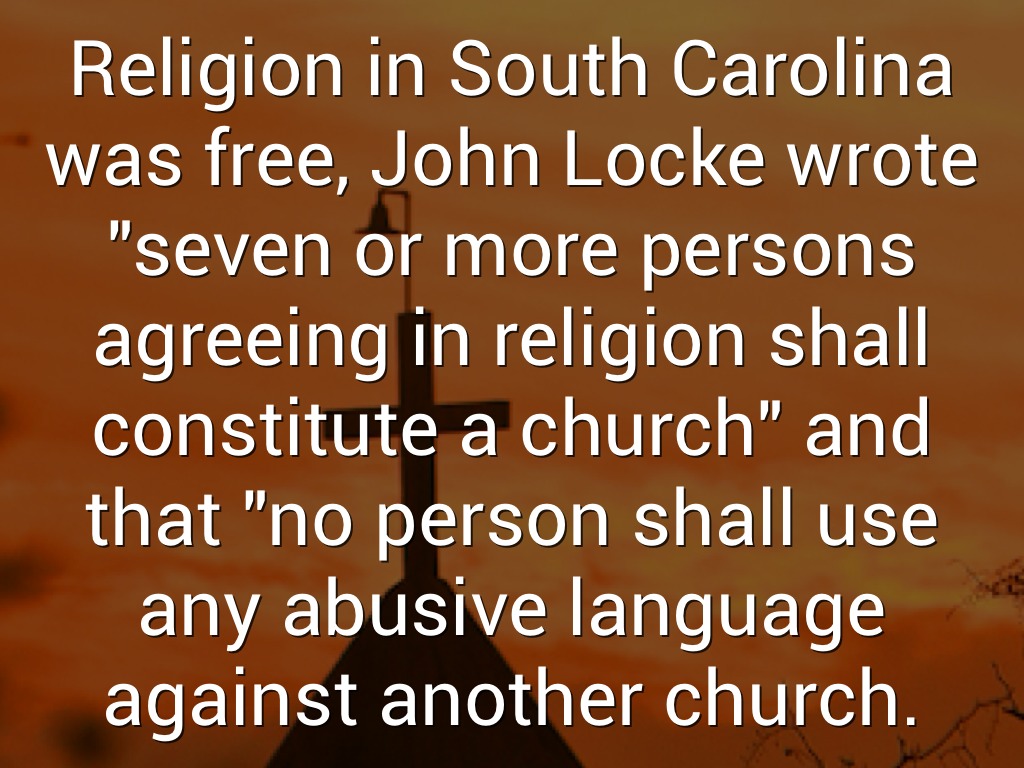

Legal Evolution and the End of Religious Establishment

For more than a century, South Carolina maintained a legally established church. However, the drive for greater religious liberty gained momentum in the late 18th century. The South Carolina Constitution of 1778 ended tax-based support for clergy and granted legal equality to all Protestant churches. By 1790, a new state constitution prohibited religious tests for public office and guaranteed the free exercise of religion for all, regardless of denomination-though with caveats related to public order and morality [3] .

This transition reflected both Enlightenment ideals and practical considerations: the colony’s economic and demographic growth depended on attracting a diverse array of settlers. While Anglicanism no longer enjoyed official status, Christianity-particularly Protestantism-remained deeply woven into the state’s culture and laws.

Accessing Historical and Genealogical Resources

If you are interested in learning more about the religious history of South Carolina, or tracing family roots tied to specific faiths, several resources are available:

Source: discover.hubpages.com

- Visit the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in person or search its online catalog for parish records, church registers, and legislative documents. Use search terms like “Church of England South Carolina,” “Huguenot records,” or “Baptist congregations.”

- Contact local historical societies, such as the Charleston Historical Society , for guidance on colonial church sites and records.

- Many churches founded in the colonial era still operate today. You can reach out directly to St. Philip’s Church (Charleston), St. Michael’s Church (Charleston), or historic Huguenot and Presbyterian congregations for archival materials.

- For African American religious history, explore institutions like the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture at the College of Charleston, which maintains collections on Gullah traditions and black religious life.

- To understand current religious diversity, consult the Interfaith Partners of South Carolina website, which offers educational resources and public programs [4] .

When seeking records or research support, be prepared to provide as much detail as possible-names, denominations, locations, and approximate dates-to improve your chances of finding relevant information.

Challenges and Alternative Approaches

One key challenge in studying colonial South Carolina religion is the scarcity of records for marginalized groups. Enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples left few written accounts, and white authorities often ignored or suppressed their religious expressions. Oral histories, archaeological studies, and cultural anthropology can provide alternative pathways for uncovering these stories. Collaborate with academic researchers or university special collections for access to such materials.

For those interested in religious legal history, reviewing legislative acts and constitutional documents can offer insights into how faith influenced the law-and how legal changes shaped religious life. Libraries at major universities, such as the University of South Carolina and the College of Charleston, are valuable starting points for such research.

Summary and Key Takeaways

The religious landscape of colonial South Carolina was complex and evolving. The Church of England held official status for over a century, but practical needs and demographic diversity encouraged tolerance of a range of Protestant groups. Enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples maintained their own religious traditions, often blending them with Christianity in creative ways. Legal reforms in the late 18th century established religious liberty in law, though the cultural dominance of Christianity, especially Protestantism, continued. Today, understanding this history is vital for appreciating South Carolina’s unique religious character and for navigating its rich genealogical and cultural resources.

References

- [1] Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (n.d.). The Landscape of Religion in Colonial South Carolina.

- [2] Charleston County Public Library (2020). The Myth of the Holy City.

- [3] Columbia Law School (n.d.). The Established Church in South Carolina.

- [4] Interfaith Partners of South Carolina (n.d.). SC’s Diverse Religious History.

- [5] Constituting America (2019). Remaining Early States’ History of Religious Freedom and Disestablishment.